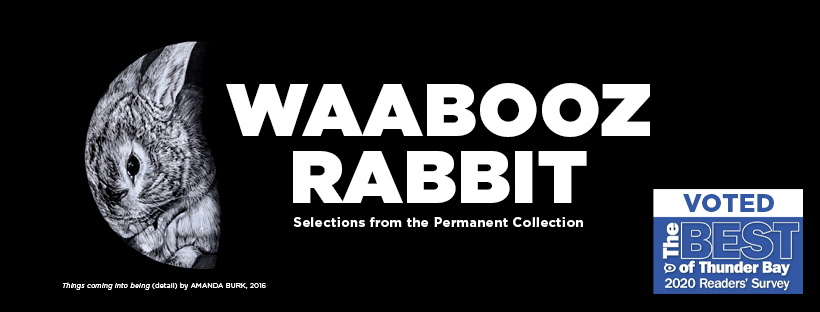

Waabooz/Rabbit

Waabooz/Rabbit

VOTED BEST ART EXHIBIT 2020

by The Walleye

The rabbit features regularly in storytelling —in myth, legend, religion, history, or pure imagination. Stories of rabbits —waabooz in Anishinaabemowin, lapin in French, wapoos in Cree— are often told to children to share wisdom, issue warnings or to amuse and delight. Nanabozho, the Moon Rabbit, Br’er Rabbit, Bugs Bunny, Peter Rabbit, the March Hare, the Velveteen Rabbit, the Easter Bunny and others have been introduced through stories and popular culture around the world. The rabbit may play the part of an animal, but usually it is given human traits —brave or cowardly, cunning or dumb, innocent or sexual, cute or fierce, domestic or wild. Much like humans, the representations of rabbits are contradictory.

Waabooz/Rabbit takes a deeper look at the rabbit, how it has been seen, spoken of, used and reproduced through art and craft. All of the rabbits in this exhibition have received some kind of human attention —from the interpretation of the artist, the hand of the hunter, the tools of the maker, the words of the storyteller, or a combination within the gaze of an audience.

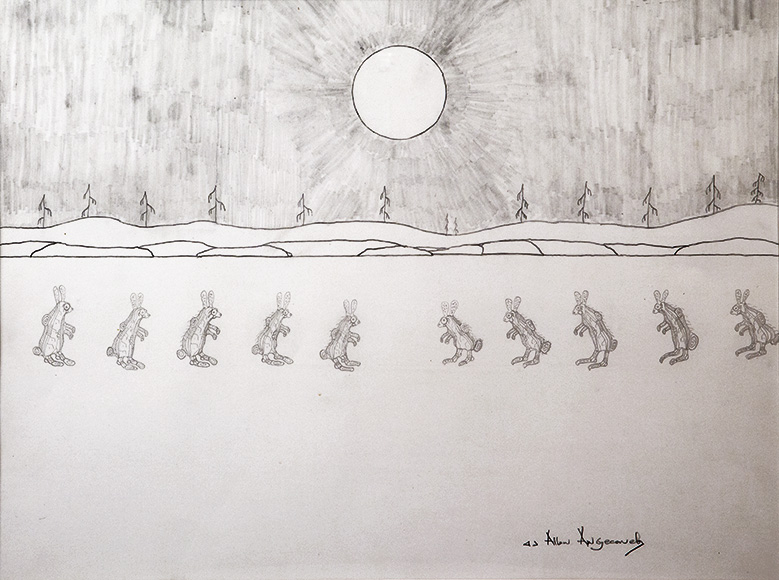

Hares and rabbits are often mistaken for one another, and indeed, the differences can seem minimal. Hares tend to be larger and lead relatively solitary lives, while rabbits are smaller and live in warrens or burrows in large social groups and have subsequently been linked to fertility. On Delia Beboning’s Circular Rabbit Quill Box (c1980) the single animal is reminiscent of the hare. While the repeating images in Ahmoo Angeconeb’s 10 Rabbits and Angelique Merasty’s birch bark bitings, suggest larger family groupings. These two artists give the rabbits an almost ephemeral nature as if to say that while there are many the creatures are also barely there at all.

Nanabozho (or Nanabush), the Anishinaabe spirit, often appears in stories in the shape of a rabbit. These stories told by knowledge keepers contain wisdom, history, and inspiration. Though Blake Debassige’s Nanabush Taking Wisdom from Crow (1975) doesn’t show Nanabozho in rabbit form, it provides a glimpse of this impressive figure, who is also called a hero, trickster, friend, teacher – many of the roles also given to rabbits.

Around the world, artists and storytellers have been fascinated with the moon. While some people see a man in the moon, others see a rabbit. Two very similar stories of the rabbit in the moon developed independently, one an Indigenous Aztec legend, the other a Buddhist tale. Each tells of a rabbit selflessly offering itself to save the life of a starving god. In gratitude and appreciation, the god draws the likeness of the rabbit on the moon for all to see. Intentionally or not, Amanda Burk invokes the Moon Rabbit in Things coming into being, with the rabbit nestled comfortably within the moon.

Amanda Burk, Things coming into being, 2016, white charcoal on paper, 38.1 x 419.1 cm, Purchased with the support of the Elizabeth L. Gordon Art Program, a program of the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation and administered by the Ontario Arts Foundation

Rabbits are prey animals as well as a source of food for humans, resulting in them often portrayed as innocent or to represent innocence itself. The opposing view of the rabbit shows it as cunning, highlighting the animal’s speed, both physical and mental, and ability to outrun or outwit those who would trap or hunt it – such as wolves, fishers, eagles or humans. Norman Moonias captures a moment in time with his Untitled [rabbit hunter] (1979); the carved wood holds the story of the success or failure of the hunt. Maybe the rabbit gets away. There is no question about whether the animal escapes in Shannon Two Feathers’ Untitled [rabbit hunter] (c1980). The hunter is bringing the rabbit home, to eat, to share, and to prepare the hide for use as warmth and decoration. The level of detail and craft used in works such as Alice Bernarde’s Traditional Gun Case (1992) and Frank Archibald’s Snowshoes (c1980) reinforce that hunting is necessary for survival but it is more than that.

Shannon Two Feathers, Untitled [rabbit hunter], c1980, oil on canvas, 51 x 61 cm, Gift of the Government of Saskatchewan

In Alec McCauley’s Old Man Thinking Back (1982) memories of a life on the water, the geese, moose, beaver and rabbit are made tangible. Among these is the rabbit, small and seemingly inconsequential, but the importance here is evident. From a long life, the rabbit is pulled forward in memory and recorded here to be included in the tradition of human storytelling, image making, and meaning.

curated by

Meaghan Eley